Once you have sparked your imagination with a writing prompt then it’s time to chose a writing form. Have fun experimenting with the many options below!

Rhyming poetry

Mention the word poetry and the concept of rhyme jumps into many people’s minds. Rhyme and metre* have been at the heart of poetry for centuries. Recognised rhyme schemes include:

- Alternate rhyme – where alternating lines in each stanza** rhyme

(A B A B / C D C D / E F E F…)

- Monorhyme – where every line ends with the same rhyme

(A / A / A / A…)

- Rhyming couplets – where the poem is made up of rhyming pairs

(A A / B B / C C…)

- Enclosed rhyme – where each stanza** begins and ends with the same rhyme, while a rhyming pair sits in the middle

(A B B A / C D D C / E F F E…)

* The pattern of rhythm within a poem

** A group of lines within a poem. In rhyming poetry this group is defined by the poem’s rhyming and metrical patterns

Free verse poetry

Free verse has no predefined structure. It does not have to rhyme or conform to a particular shape or metre*. However, rhyme and patterns of rhythm can be woven in at the poet’s discretion.

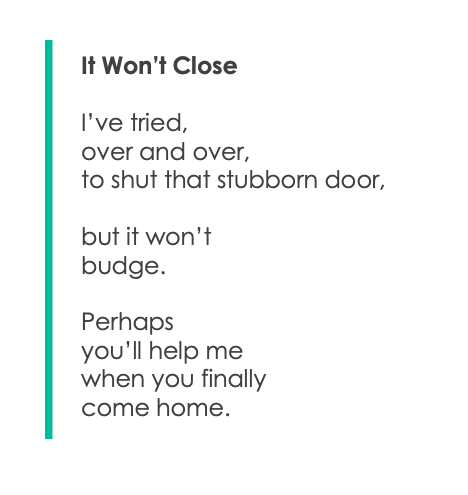

Some free verse poems take on the rhythms of ordinary language. The poet chooses where to place line breaks and how to organise the stanzas*. These decisions can help to give individual words and phrases more emphasis, as in the following example:

* The pattern of rhythm within a poem

** A group of lines within a poem. In free verse this could be likened to ‘a paragraph’

List poetry

This form of poetry involves creating a list of entries that all relate to a chosen topic. The items on the list can be anything from objects or people, to feelings or ideas. The list builds until it reaches an item that is particularly significant – one that might be poignant, amusing or thought-provoking.

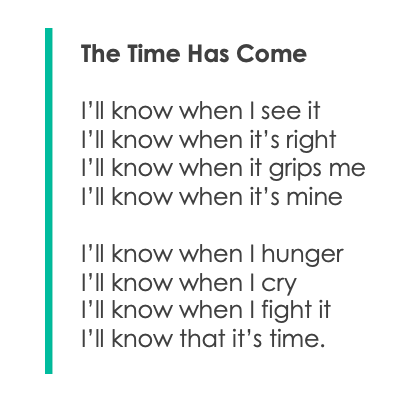

A list poem can be written as a straightforward inventory, perhaps involving some repetition as in the below:

Alternatively, the list can be woven into a pattern that reads more like a story:

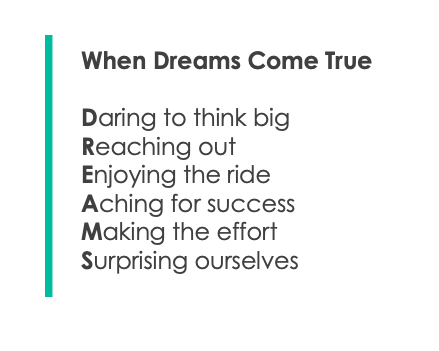

Acrostic poetry

In an acrostic poem, each line of the poem includes one letter from a chosen word or phrase. When the poem is complete, the individual letters can be read vertically down the page to spell out that word or phrase. Most often, the letters will be at the beginning of each line, as in the example below, but they can also be in the middle or at the end. The chosen word or phrase is usually linked to the main theme of the poem.

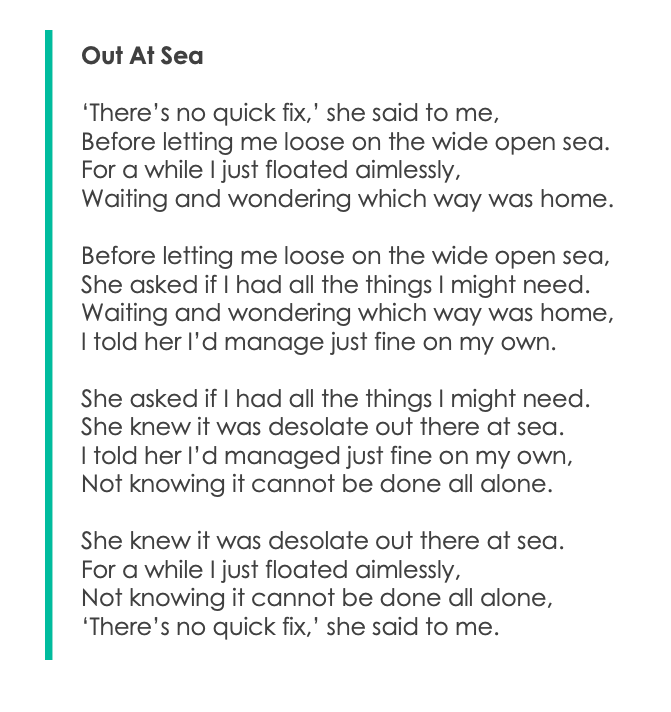

Pantoum poetry

The pantoum, as we know it today, evolved from a fifteenth century form of Malaysian verse. It follows a set structure, where lines are repeated in various positions throughout the poem. The effect can be surprising. The repeated lines take on new weight and meaning as they appear in different contexts. There is some variation in the number of stanzas and the exact pattern of the repetition. A popular pantoum structure is as follows:

Pattern of repetition

Line 1

Line 2

Line 3

Line 4

Line 2 (repeated)

Line 5

Line 4 (repeated)

Line 6

Line 5 (repeated)

Line 7

Line 6 (repeated)

Line 8

Line 7 (repeated)

Line 3 (repeated)

Line 8 (repeated)

Line 1 (repeated)

Here’s an example of the pantoum pattern in action:

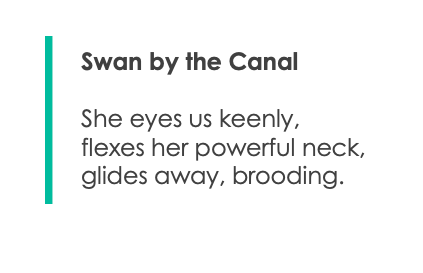

Haiku poetry

Originating from a form of traditional Japanese poetry, modern haikus involve a very tight structure – just three lines, totalling seventeen syllables. Traditionally, haikus were used to capture the essence of a moment from the natural world. Today, they are written on a wide variety of topics. The haiku format is as follows:

Line 1: 5 syllables

Line 2: 7 syllables

Line 3: 5 syllables

A finished haiku might look like this:

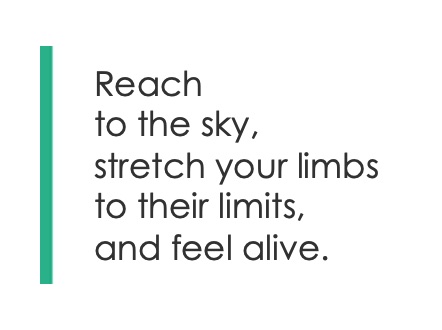

Gogyohka poetry

A gogyohka is a five-line poem where each line represents a single phrase, or ‘breath’. There are no restrictions on how many syllables are in each line and there is no need to make the lines rhyme. The aim is be concise, however, and to keep lines as short as possible.

Originating in Japan, this flexible form of poetry was created by poet Enta Kusakabe. It evolved from more traditional Japanese forms such Haiku and Tanka.

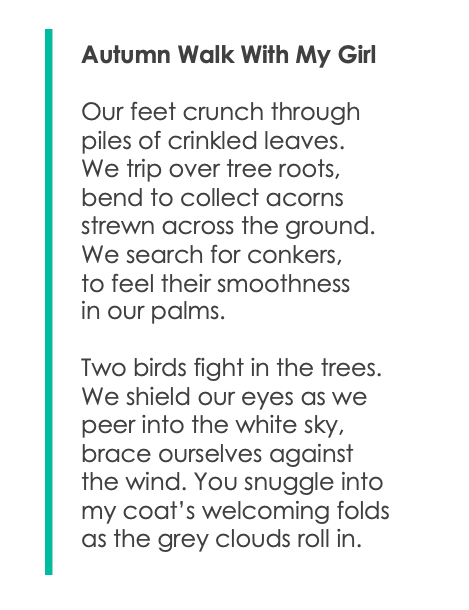

Here’s an example:

Prose

Prose is the type of writing we’re used to seeing in our ordinary lives. It lies at the heart of many creative writing forms, from flash fiction and short stories to novellas, novels and more. Unlike poetry, it is not broken up into verses and lines or based around metre or rhyme. Instead, it follows the natural rhythms of spoken language.

Dialogue

A conversation between two or more characters. These ‘characters’ may be people, but if desired one or more of them could be a place, an object, an emotion or even an idea. Anything that might have something to say can be given a voice as part of dialogue writing. For example: Why did the pot call the kettle black? What might the North and South poles say to each other? What might Happiness say to Sadness? What would the traveller say to their hometown? What would the house say to the family living in it?

The dialogue can be written as part of a wider piece of prose:

Alternatively, the dialogue can be written out exactly as it would have taken place:

From here, the dialogue could be evolved to take on the shape of a radio play, stage play or television programme if desired.

Diary entry

Taking the form of a diary or journal entry, this type of creative writing is generally in the first person and often anchored to a particular point in time. The content can be factual or reflective and the topics covered can vary widely, from events of the day through to deeply personal insights.

Personal diaries are often written for the author alone to read, with no other audience in mind, and the writing itself might reflect that. As a result, some of it could appear particularly vulnerable or revealing – words that might never be uttered out loud.

Letter

Written from the sender’s point of view, a letter is created specifically with the recipient in mind. In creative writing, these two players can be people, objects, places or even emotions or concepts. Someone suffering from chronic pain might write a letter to that pain in an attempt to come to terms with it; a person concerned with the environment might write a letter to the Earth; or the Earth might write a letter to the human race!

Postcard

Postcards offer a snapshot of the sender’s experience. They can be factual or reflective, humorous or poignant. When writing creatively, the sender and recipient can be people, objects, places, emotions or concepts – any entities that might like to communicate.

Creating a postcard from scratch can be a fun way to combine both art and writing. Draw, paint, or cut out a photo from a magazine and use your piece of art as the focus for a picture postcard.

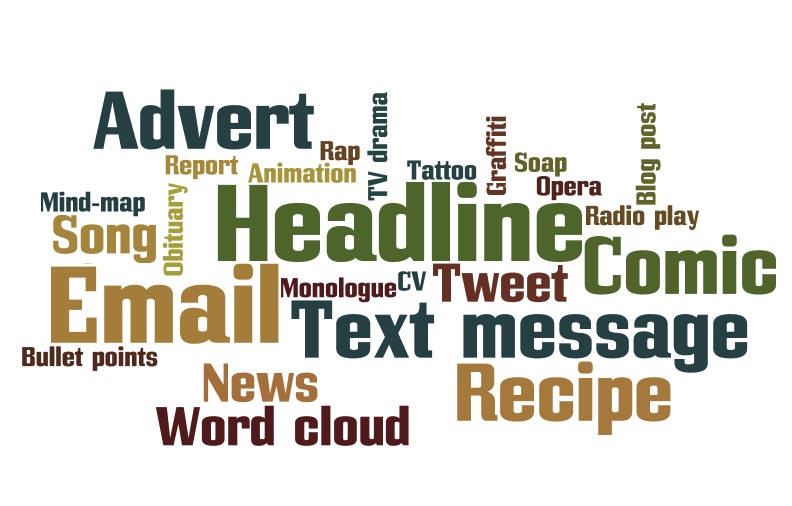

And more!

The word cloud below includes further suggestions for writing forms.